Fights (Part 1/2) -

My Kids Are In the Middle of One!

A parent recently wrote: I'm having trouble with hitting. Do you have a P.E.T.-approved way to stop physical violence between brothers?

This is tough!

In this post, we'll do a skills walkthrough on how to help -- let's call them -- Sean and Jack; in the next, we'll work on prevention.

It might help first to normalize sibling strife. As US parenting expert and author Laura Markham writes, brothers and sisters are wired to compete with each other: “Their genes want to know whom you would save if a tiger came marauding. If you love their sibling more, they’re toast.” (Peaceful Parent, Happy Siblings: How to Stop the Fighting and Raise Friends for Life, page 161). Despite our best efforts, some rivalry will exist.

But when Sean hauls off and hits Jack, where should we start?

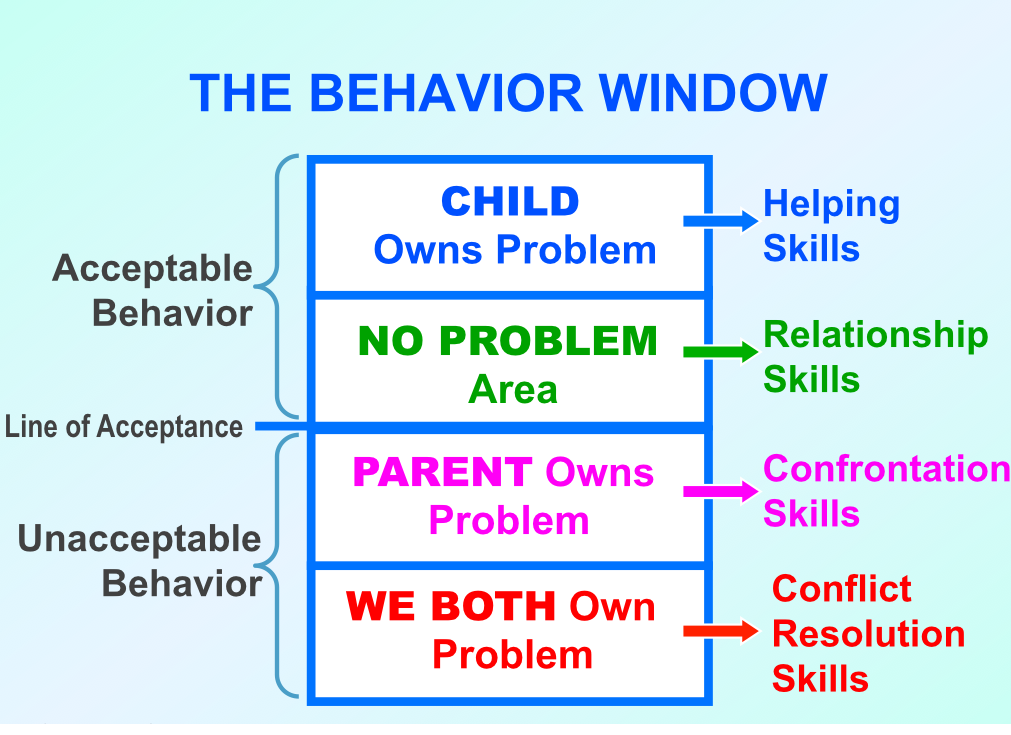

With the Behavior Window and the mother of all guiding questions: Who owns the problem?

Problem Ownership

Child Owns Problem?

Yes.

Sean is showing in behavior -- and maybe he branches out to kick, scratch and bite! -- that he has big, upset feelings and some need he is not able to meet.

No Problem?

Definitely not.

Parent Owns Problem?

No.

A Parent Owns Problem example would be, say, Sean unperturbedly going about his business of stacking empty glass jars on the tiled kitchen floor. The child is fine but we are worried about the mess and the possible visit to the emergency room.

Both Own Problem - Conflict of Needs?

No.

We may feel angry and irritated at Sean but there is no concrete and tangible effect on us.

One might argue that our needs ARE involved when one of our children is creating a physically unsafe situation for the other. This reasoning stresses the security, efficacy and self-esteem that come from successfully protecting our offspring.

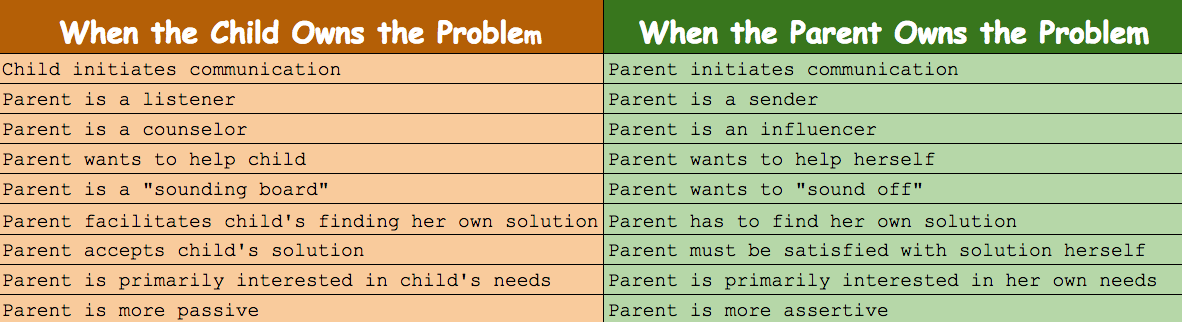

But consider how our role shifts when we are trying to meet our needs:

Thomas Gordon, Parent Effectiveness Training: The Proven Program for Raising Responsible Children, page 118

If we operate with a Child Owns Problem mentality, we get the immediate behavioral change we want AND foster self-control and empathy that he can drawn on in similar situations in the future.

In contrast, striding in and "owning" the problem (however reasonable we think we're being) fails these short and long-term goals. It also undermines relationships -- between child and parent and between siblings!

““When one child ‘wins’ the argument because of parental intervention — and make no mistake, both children do see the parent siding with one child as that child winning — the ‘losing’ child becomes resentful and more likely to initiate another fight . . . Siding with either child pushes the other child away from you. After all, she thinks she’s right. Even if she’s four and she’s yelling at her eleven-month-old sister for looking at her toy. When you side with her sister, it convinces her that you love her sibling more, which intensifies the feelings that triggered her aggression to begin with. When you take sides in any way — even if you’re objectively right — one child feels like she’s won and one feels like she’s lost, which feeds the rivalry.” ”

Both Own Problem - Conflict of Values?

Perhaps, but not really.

We value assertive, over aggressive, behavior. The thing is, I think Sean does too; it's more lack of skills than a difference in beliefs or ideals that's shaping his behavior.

When we equip Sean with alternative ways to deal with his overwhelming anger, he slowly grows the awareness and communication skills that allow him to live non-violently.

Either way, we can certainly share our values through modeling and consulting! (See #3 and #7.)

The Game Plan

It should be mentioned that before it gets physical and they come to us with the dreaded, "Mommy/Daddy, Sean says I can't use the markers to draw!" Gordon says the first option is to let kids try to solve the problem themselves. We can say "“I trust you guys can work it out,” and then hang around to coach if needed.

When the sharp elbows start flying, that's when we take a more active role.

(Non-intervention might be seen as implicit endorsement of the behavior which may lead to more frequent or aggressive conflict, according to Markham on page 97 of her siblings book -- see Resources.)

1. Stop the aggression with a concise I-Message & firm, yet gentle, touch

If Sean is hurting Jack, we quickly separate by using the minimum force necessary. (This is different from using power to punish; here our greater might only sets a limit to keep both kids safe.) We firmly but gently hold Sean back. Touch like this can help him feel connected and calmer.

We simultaneously send a clear Declarative I-message, e.g. "I don't allow hitting. Hitting hurts."

2. Move to victim - quickly Active Listen aggressor if possible

As we're moving to Jack, we see if we can muster up some empathy for Sean, "Oh, you must be very sad and mad!"

If, on the other hand, we are seeing red because our baby Jack was just pummeled, we zoom in and tend to him.

Either way, we prioritize Jack: "We all have a right to be safe in our home. I need to help Jack and then I can help you."

3. Model caring & Active Listening of victim

We hold Jack -- especially if we still want to protect him from his upset sibling -- and comfort him: "That was a real bad shock! You’re so upset."

Sean is most definitely taking this in.

4. Active Listen aggressor

Once Jack is taken care of, or if a co-parent or helper is caring for him, we can remove Sean for some quiet connection time. (If you're scoffing, "What? Reward him with positive attention?" please see Dealing with Resistance: Ours & Others below.)

We might say, "I need to take you away from Jack because hitting hurts. Jack was crying. Everyone has to be safe so let’s go to a special place to calm down." If Sean is young, we can pick him up as we move.

And then we help Sean unpack the roiled emotions that led to the physical outburst. "That was really hard when you wanted Jack’s toy. You were waiting for it but he didn’t give it to you!"

If we don't know what happened, we can simply reflect back what we know about the situation and what we guess are the underlying feelings: "You seem really down and mad! Something did not go the way you wanted!"

If Sean is silent, we just hold him and say "When you feel like talking, I'm here to listen . . . . I really want to hear how you are feeling, Sean."" He may open up after we've offered some Silence and Attended non-verbally (these are other Helping Skills).

As Sean speaks, we acknowledge what may be a gamut of emotions: powerless, jealous, sad, frustrated, etc. He benefits greatly when we Active Listen and "hear" his needs, such as acknowledgment (he was under the grip of intense emotions) and understanding (he didn’t mean to hurt Jack).

How do we know we're done?

We will sense an energy shift or emotional release. If Sean starts to cry, that's good! He might say that he wants to go make up; if he doesn't, we move in with the next step.

5. Problem-solve

Our calm behavior up until now has been appealing to Sean's higher, empathic brain and he has seen and heard the need of his brother for compassion too.

We can help Sean think of solutions to regain peace and closeness: "Gee, I wonder what you could do for Jack’s head right now? I wonder what you could say to Jack to help him feel better? Let’s check if Jack is ok and get him a glass of water."

We allow him to shift from aggressor to helper and, that way, right the wrong.

If Sean doesn’t want to go, there is no point in forcing him before he's ready. We want his actions to come from within, rather than imposed from without. Perhaps Sean just needs more time to fill his cup before he can sincerely acknowledge his mistake. Accepting this will go a long way in helping Sean make the choices he would if he felt stronger.

““It is one of those simple but beautiful paradoxes of life: When a person feels that he is truly accepted by another, as he is, then he is freed to move from there and to begin to think about how he wants to change, how he wants to grow, how he can become different, how he might become more of what he is capable of being.”

”

(Say Sean raises his hand against Jack again as soon as he sees him. We again send a strong message that, while you see the good in him, the behavior is unacceptable: "I won't let you cause pain to your brother. Ok, we are going to have to play separately so that no one gets hurt. We will definitely try later because I know you LOVE playing with Jack and are just having a tough time right now.")

If Sean is calmer, we let him make the repair he wants to.

6. Mediate

Once the brothers can be in the same space together, we can become what Gordon likened to a "transmission belt," decoding each child to the other and encouraging them to use I-Messages.

It might go something like this:

Parent: "Jack, can you say how your head felt when Sean hit it?"

Jack: "It really aches!"

Parent: "Oh, it's still painful. I can see where you're holding it . . . Sean, can you tell Jack how you felt when he didn't give you the toy?"

Sean: "I asked you three times and you weren't even answering!"

Parent: "I hear Sean saying he did try to use his words but he got very frustrated when you didn't answer."

Sean: "I got mad!"

Parent: "Sean got angry too. It was really aggravating to ask and not get an answer."

Method III Problem-solving is what Gordon called his collaborative approach that focuses on finding solutions that meet needs.

At this point, we can attempt the same problem-solve, only now with both sons: “I think there’s a way you two can work this out so you can both have fun and feel it's fair. Let’s see who has some ideas?”

Let them come up with the solutions without editing. We can keep track of them and then ask them to evaluate and choose with, "Which of these ideas sound the best?" Then we sum up: "Ok! You've decided to use the sand timer for taking turns and after you've each had a go, you wanna get out the play clay and build something together!"

We can help them with Step 6 by checking in: "Looks like you are having fun! Your plan worked!" If something has gone awry, we bring them back to the drawing table -- "Oh, I hear sounds that someone is upset!" -- and start with Step 1 again by Active Listening.

7. Consult

Later, when the incident has blown over, we can become a consultant on helping Sean to upshift from his lower brain's "fight mode" where Jack is the enemy to his higher perspective-taking and reasoning ability. Daniel Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson's The Whole Brain Child is filled with strategies in comic strip form. I like this breathing video as well.

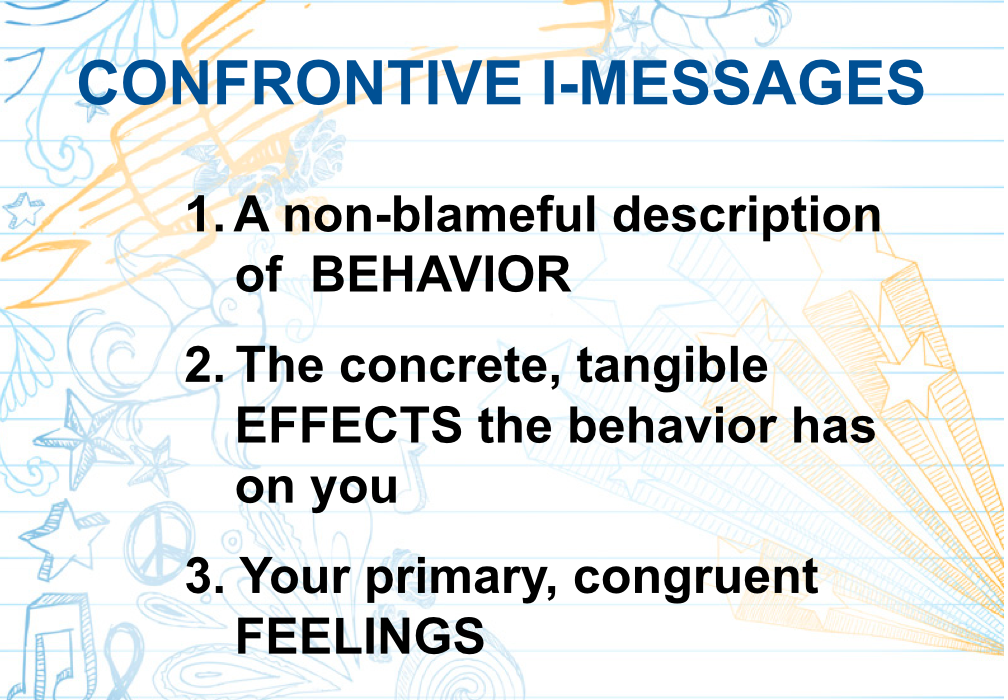

And we can explicitly share how to do effective confrontation. We can use puppets or storytelling to help Sean practice what to say the next time he feels his anger rising as he waits for his turn. Even toddlers can grasp very simple Confrontive I-Messages such as, “I no like that,” “I sad,” or “I mad at you.”

With older kids -- see example below with my teenage sons -- we can even hand out lists of feelings and needs and help them verbalize the three parts of a Confrontive I-Message:

Dealing with Resistance (Ours and Others')

The above steps help us maintain a close connection with Sean while he tries to move past his negative feelings. Our safety net helps him feel secure enough to assume responsibility for his behavior and take steps to resolve his conflict with his brother.

Are you about to slam your laptop closed? Does this seem like it will take WAY. TOO. LONG? Who has this kind of time? This is gonna be worse if there's an apoplectic co-parent goading us to "Take control already! He's gotta learn that hitting is never an option! This P.E.T. stuff is garbage."

I'd like to call on neuroscience for back up. Daniel Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson explain their P.E.T.-friendly "Connect and Redirect" approach this way:

“By demonstrating respect for your child, nurturing him with lots of empathy, and remaining open to collaborative and reflective discussions, you communicate “no threat,” so the reptilian brain can relax its reactivity. In doing so, you activate the upstairs circuits, including the extremely important prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for calm decision making and controlling emotions and impulses. That’s how we move from reactivity to receptivity . . . What’s even more exciting is what happens AFTER we appeal to the upstairs brain. When it gets engaged repeatedly, it becomes strong. Neurons that fire together wire together . . . Using her upstairs brain will more and more become her accessible pathway, her automatic default, even when emotions run high. As a result, she’ll become better and better at making good decisions, handling her emotions, and caring for others.”

So we won't always have to expend this much effort and time.

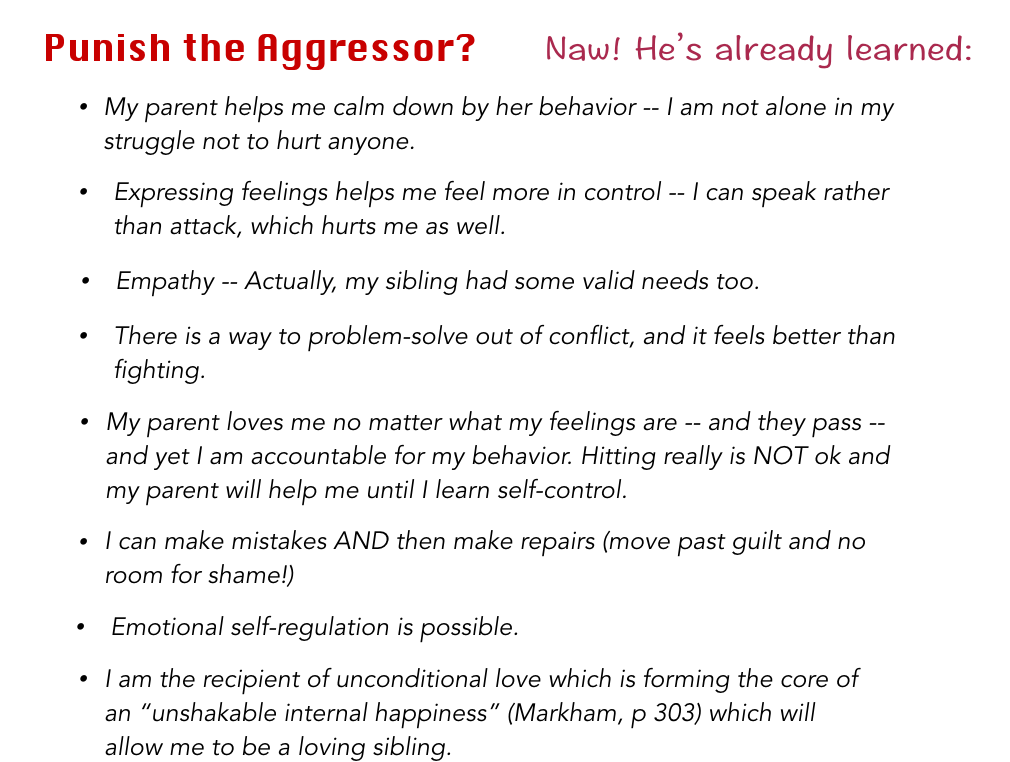

There's also the question of consequences -- Doesn't there have to be some punishment for the way Sean behaved? Actually, no, not if we keep our eye trained on our long term goal of helping him develop into a secure, happy, big-hearted individual who can temper his aggressive impulses.

Taking away Sean's iPad or, worse, spanking would distract him and undo some mighty precious lessons he has absorbed:

This slide derives from Markham's sibling book (see Resources).

Real Life Example

A few years ago, I heard some commotion from the study and when I got to the bottom of the stairs I glimpsed some pushing between Harrison (16) and Jake (14). Harrison brushed by me to go up to his room.

I looked at Jake who glared back, put on his headphones and turned to his computer.

I went in search of my eldest child. At first, Harrison didn’t want to talk, stating there wasn’t a problem and he had calmed down. “That’s one of my strong points, Mom," he claimed, "I just let it roll off me.”

I Active Listened with something like, "Yeah, you don't want to discuss it." After a pause, I consulted on the importance of self-disclosure. Otherwise, I explained, the strong emotions might well bubble up in lingering resentment.

He agreed so I drew up three columns on a scrap piece of paper and he filled them to make a Confrontive I-Message. (I don't even remember what it was!)

With impeccable timing, Jake came in, curious. I encouraged Harrison to read the behavior, feeling and effects aloud. Jake listened silently and then I helped him devise his own Confrontive I-Message which Harrison accepted.

That was all it took; they didn't need to problem-solve that time. It was enough that each brother had acknowledged the other's side of the disagreement. Harrison and Jake started chattering and horsing around for another hour and I didn't sweat the fact that it was past bedtime.

I was living and breathing what Gordon noted and I wasn't going to cut that short.

Other Resources

If you want to read another P.E.T. based instructional post, I love long time instructor Larissa Dann's entry called Secrets to Sorting Sibling Squabbles.

Peaceful Parent, Happy Siblings: How to Stop the Fighting and Raise Friends for Life by Laura Markham. This excerpt on her website discusses punishment and gives helpful language for a three year old toddler.

The Whole Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child's Developing Mind, Survive Everyday Parenting Struggles, and Help Your Family Thrive by Daniel Siegel & Tina Payne Bryson

No-Drama Discipline: The Whole-Brain Way to Calm the Chaos and Nurture Your Child's Developing Mind by Daniel Siegel & Tina Payne Bryson

Thanks to My Mentor

A big thank you to Kathryn Tonges who guided me in my early days of being a P.E.T. instructor with her wealth of experience as an early childhood educator and instructor herself. The walkthrough described here largely comes from coaching sessions with her. Check out her website.

Credits: Kids fighting (http://hellodoktor.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/shutterstock_307613663.jpg